Author’s note: This is the second part of my analysis of modern pluropoly in the United States. You can find Part 1 here.

I look forward to your comments.

Choose any color (as long as it’s black)

Imagine you’re at the supermarket, picking up some of the items your family needs. You look at the fully stocked shelves and think how lucky we Americans are to have so many choices.

You could choose Crest or Oral-B toothpaste, Pampers or Luvs for the baby, Cheer, Tide, or Gain to clean your clothes, shaving cream from Old Spice or The Art of Shaving, razors from Braun or Gillette, or Dawn or Ivory for your dishes. There are so many choices!

Except that every one of those brands is owned by Proctor & Gamble. So, while you believe you have choices, the executives at P&G don’t care what choose — they make money either way. They have created the appearance of competition when, in reality, there is very little.

In fact, just 12 corporations own more than 550 consumer brands.

Moreover, there’s a very good chance that the grocery store you went to was owned by one of just four companies: Walmart, Kroger (including Harris Teeter & Ralphs), Albertsons (including Safeway), or Ahold Delhaize (including Food Lion, Giant, and Stop & Shop). These four corporations own roughly 60% of all the grocery stores in the U.S.1

No one else can play.

If this grocery hegemony angers you, why not just open your own grocery store (you could call it “Mom & Pop Shop”)? It’s America, after all, and if you can offer better prices and services, you should be able to compete, right?

Wrong.

Because of their massive size, these companies can pressure suppliers to give them better prices. If you’ve ever heard stories or read articles about big box stores driving smaller, locally-owned stores out of business, this is what they were talking about.

Here’s an over-simplified example of how this works:

Walmart tells Proctor & Gamble that they will only carry Crest toothpaste if P&G sells it to Walmart for $3.00 a tube. Because Walmart is the largest grocery retailer in the country, P&G agrees, even though it will only make, say 50¢ profit on each tube of Crest sold at Walmart.

Walmart then sells that tube of Crest to you, the consumer, for the “everyday low price” of $6.50. Let’s assume Walmart’s other costs (wages, marketing, etc.) add up to $2.50 per tube, making the company a $1.00 profit on each sale.

Now it’s your turn. When you want a supply of Crest to sell at Mom & Pop Shop, P&G gives you a firm price of $4.00. After all, you only need a few dozen units a month, not the millions of units Walmart sells.

And since P&G only makes 50¢ per tube from Walmart, they need to increase their profit elsewhere. They’ll make $1.50 per tube from you.

So you pay $4.00 per tube of Crest. Even if you can keep your other costs to $2.50, like Walmart, your break-even price is $6.50. In order to make a profit, you are forced to charge more than Walmart’s “everyday low price.”

In other words, you will go out of business if customers aren’t willing to pay the higher prices at Mom & Pop Shop instead of saving money at Walmart.

Breaking the law.

If all of this sounds unfair, you won’t be happy to hear that Walmart's pricing pressure is actually illegal. The same is true for Kroger, Albertson’s, Home Depot, and all other big box stores.

You see, this has all happened before, in the 1930s. At the time, Congress realized this kind of pricing pressure was anti-competitive, so it passed a law called the Robinson-Patman Act. Stacy Mitchell explains the law in a recent article in The Atlantic:

The law essentially bans price discrimination, making it illegal for suppliers to offer preferential deals and for retailers to demand them. It does, however, allow businesses to pass along legitimate savings. If it truly costs less to sell a product by the truckload rather than by the case, for example, then suppliers can adjust their prices accordingly—just so long as every retailer who buys by the truckload gets the same discount.

The law helped even the playing field, and by 1982, the largest eight grocery chains owned 25% of the stores. Thus, nearly every urban neighborhood and small rural town had at least one grocery store, and most of these stores were owned by local individuals or small chains.

So, why did Congress repeal the law?

They didn’t. The Robinson-Patman Act is still the law.

During the Reagan Administration, the government just stopped enforcing it. And no administration since has started again.

This has led to the grocery monopolies we experience today and the “food deserts” that exist in poorly urban neighborhoods and rural towns across the U.S.A. (Read Mitchell’s entire article to learn more.)

So, when the price of groceries goes up, it may have more to do with the monopolies that control the grocery stores and the products they sell. Or maybe it is the fault of the Party in the White House since none of them, Democrats or Republicans, have seen fit to enforce the laws of the land for over 40 years.

They Own Everything

Groceries are just one sector, and monopolies are a real problem in that sector. America’s problem with capitalism, however, goes beyond sectors. Here’s a story to illustrate.

Chapter I: Back in the late 1980s, I shopped at a small grocery store on North Lamar Boulevard in Austin, Texas. The store sold organic produce and healthy household products, everything a young liberal could ask for. In fact, it was more than just a store — it was the center of a community of like-minded people. It was called Whole Foods Market, and I loved it.

By the early 1990s, there were a few other locations in Texas and Louisiana, and the company went public. (Capitalism! Yeah!) My family and I continued to shop at Whole Foods when we moved to the D.C. area a decade later, and we still do today here in East Tennessee.

Chapter II: Ten years ago, while living in the D.C. suburbs, I was frustrated by my choices in doctors’ offices. Like many people, I often found that a 10:00 am appointment meant that I didn’t actually see the doctor until closer to 11:00 am, and a simple annual checkup could cost me the better part of a day. Then I heard about a different kind of doctor’s office called One Medical.

I joined One Medical for an affordable annual membership fee, and for the next seven years, my doctor’s appointments started on time, and an annual checkup rarely took more than an hour out of my day. It was truly a better healthcare experience.

Chapter III: Of course, as residents of the Washington, D.C. area, our local newspaper was the esteemed Washington Post. We had it delivered for years and still subscribe to the online version today (though somewhat reluctantly) even though we no longer live in the area.

Conclusion: In 2013, Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon, Inc., bought The Washington Post. In 2017, Amazon, Inc. bought Whole Foods Market. In 2021, Amazon, Inc. bought One Medical.

My newspaper, grocery store, and doctor’s office are essentially all owned by one guy.

Do you like movies? Amazon owns MGM and IMDb.

Do you like books? Amazon owns Audible, Goodreads, and AbeBooks.

Do you like video games? Amazon owns Twitch.

Do you have a Ring doorbell? Amazon owns Ring.

Thinking of buying a new Hyundai? You’ll likely go through a new Amazon-owned service to find a dealer.

Amazon owns a driverless car company, a robotics company that manages inventory delivery for other retailers, a physicians system, an online pharmacy, and the list goes on and on. (By the way, Amazon has also received more than $5.8 billion in government subsidies, but that’s another story.)

Maximizing Profits by Minimizing Competition

It’s not just Amazon. Apple, Alphabet (Google), Meta (Facebook), and others own and are acquiring companies across multiple sectors. This represents a fundamental change in how consumer-facing businesses and investors think about profits.

Once upon a time, companies succeeded when consumers paid for their products and services. For example, the Yummy Snack Company (not a real company) would research consumer spending habits and determine that 10¢ out of every dollar the average American household spends on food goes to buying snacks. The company would design its products and marketing plans with a goal of earning 2¢ of that.

If Yummy Snack Co. succeeded, the average American household would spend 20% of their snack budget on Yummy products, and the shareholders would be happy.

Then Megabrand comes along and buys Yummy Snack Co. They buy shoe stores, a chain of oil change stores, a company that makes diapers, and everything else they can get their hands on.

Megabrand’s strategy isn’t to get 20% of your snack-buying budget. Megabrand wants 20% of every dollar you spend. Now, replace “Megabrand” with Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Apple, etc., and you see what I mean.

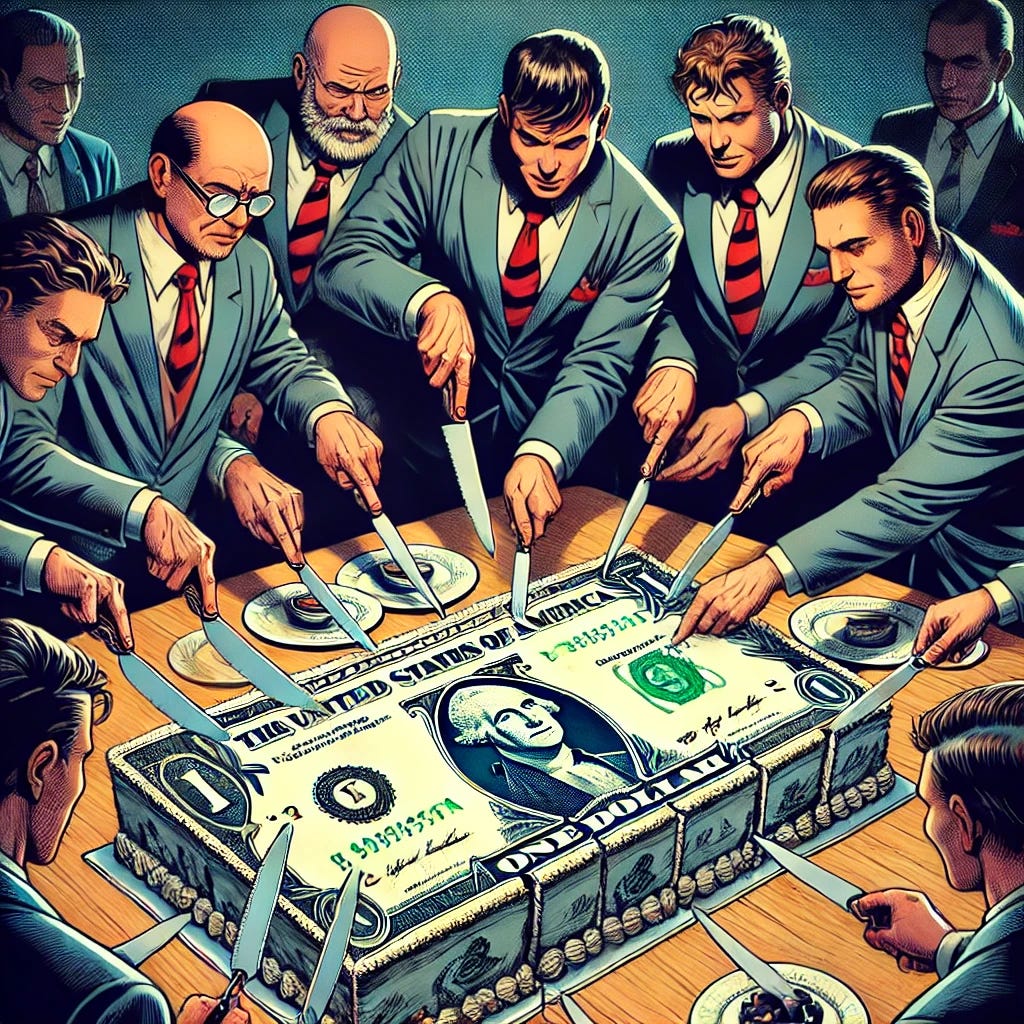

In other words, we’re not just experiencing monopolies within sectors like groceries. We’re experiencing monopolies of monopolies, in which a substantial portion of every consumer’s spending across all sectors is going to just a handful of companies.

There is no universe in which this kind of pluropoly is in consumers’ best interests. In fact, it’s widely accepted that Big Tech is now stifling the kind of innovation that capitalism is supposed to encourage.

How the U.S.A. Abandoned Capitalism, Part III will be out soon. If you think someone you know would find this article interesting, please share it.

In case you were unaware, Kroger and Albertsons recently attempted to merge. Fortunately, it appears that isn’t going to happen.

Not subscribing yet but maybe after this series of articles. Part two is great.